New paper: Microbes, methane, and global warming

My latest paper was published in its final form last week. It’s been a long wait! Feel free to take a look at the paper itself, or read on for my thoughts.

The story

It was several years ago that microbes first caught my attention. Microscopic life forms: bacteria, fungi and many more, live beneath our feet and these tiny little living beings, in their astronomical numbers, are engineers of the Earth’s climate.

In total, they emit greenhouse gases at around six times the rate that humans do. The reason that this hasn’t caused a huge problem is because it’s part of a closed cycle. Microbes release carbon from the soil (in the form of greenhouse gases), and plants absorb it and put it back in again, in a continuously cycling loop. Interrupting this loop, by removing plants, for example, can lead to an imbalance and to more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Climate change might also lead to an imbalance, since there’s no reason to expect that microbes and plants will react in the same way to global warming. This is something we are pretty worried about, because if global warming causes huge carbon emissions from the soil, this could jeopardise our efforts to keep climate change below safe levels.

Aside from concern about the future, what motivates me as a scientist is trying to understand things that are currently a mystery.

In 2014, a colleague showed me how modelling the behaviour of microbes leads to really interesting patterns of carbon emitted from the soil. For example, when you warm it up you get a very strong, quick emission of carbon that all-but stops after a few years. It’s difficult to measure this, but the measurements we do have do give a clue that this might be happening in the real world too. In contrast, climate models, which we use to predict the future, model soil emissions in a very simplified way and don’t show this pattern at all.

At the time I thought “This is a big deal”, and being relatively new to climate science back then I wondered if this was where I could make a meaningful contribution. Ever since then, I’ve been thinking on and off about modelling microbes. This is no mean feat. Starting with minimal knowledge of microbiology (I’ve always wanted to study biology…), I have invested a lot of time in the last few years into reading microbiology papers, and barely scratched the surface of this incredibly complex world.

The paper

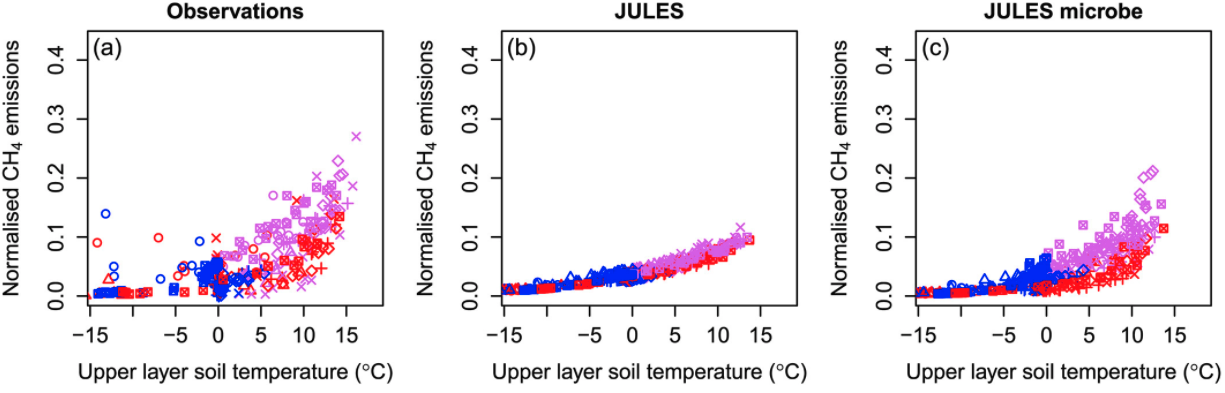

For my new paper, which is my first study on microbial modelling (I mentioned it’s been a long brewer), with the help of my co-authors I focused on the relatively ‘simple’ case of methane-producing microbes. Painstakingly, I compiled information from all sorts of different studies and converted them into equations to represent the dynamics of these microscopic life forms. I also analysed a lot of data on methane emissions from soils as measured by several-meters-high towers above the ground. And, using the microbial model I found that I could explain some of the mysterious behaviours that are seen in methane emissions above ground. In doing so I had linked the microscopic with the macroscopic world. We propose a new scientific hypothesis based on the model results.

I find it really exciting to be pushing forward scientific knowledge, even if it’s only a little bit at a time. A little bit at a time is how you eventually get a long way. But of course, with something as immediate and urgent as climate change, there isn’t much time.

More to do

In my paper I modelled methane emissions globally, and found a 12% increase in methane emitted from the soil for every one degree Celsius of global warming.

However, my modelling really focused on the effects of temperature on methane production. To be confident about what will happen to methane in future we need the effects of water to be included too. I made a small start on it in the paper but there’s more to do, which would be a nice project for a masters or PhD student…

Then, there’s the much bigger step to extend this from the ‘simple’ case of methane production to model the whole carbon cycle. This is the subject of my first grant proposal which I submitted in the summer and would pay for two researchers to work on it full time for 3 years. The chances of getting funded are small, but I don’t think that is any reflection on the importance of microbes for the future of our planet (maybe more on my level of experience with writing proposals). Six years since that initial moment of “Wow, this is important” and I am more convinced than ever that micro-organisms are a big deal.

A graph from the paper showing methane (CH4) emissions at different temperatures, in reality (left), in a typical climate model (middle), and in the new model with microbes included, which matches the real world much better (right).

A graph from the paper showing methane (CH4) emissions at different temperatures, in reality (left), in a typical climate model (middle), and in the new model with microbes included, which matches the real world much better (right).