Fieldwork in Iskoras

At the beginning of September I joined Hanna and her team at their field site in Northern Norway. The team has set up a study site in the lowlands - where permafrost is found - and named it ‘Iskoras’ after the hill nearby.

This place is a long way from anywhere I would normally find myself, both physically and metaphorically. After flying to Tromsø in a fairly small plane, we transferred to an even smaller one to make the hop to Lakselv, which is a tiny town which nonetheless (surprisingly) has a ‘Vinmonopolet’ so we could buy wine for the week. After this, we drove for an hour to reach our campsite, where we stayed in a cosy cabin. Another 40 minutes drive took us out into what seemed like the middle of nowhere. This is a landscape of rolling hills blanketed in small birch trees, opening out now and then into patches of Arctic tundra, with the trees already turning yellow for autumn. The road became a gravel track, and eventually we had to leave the car and hike for the last two kilometers to the field site itself.

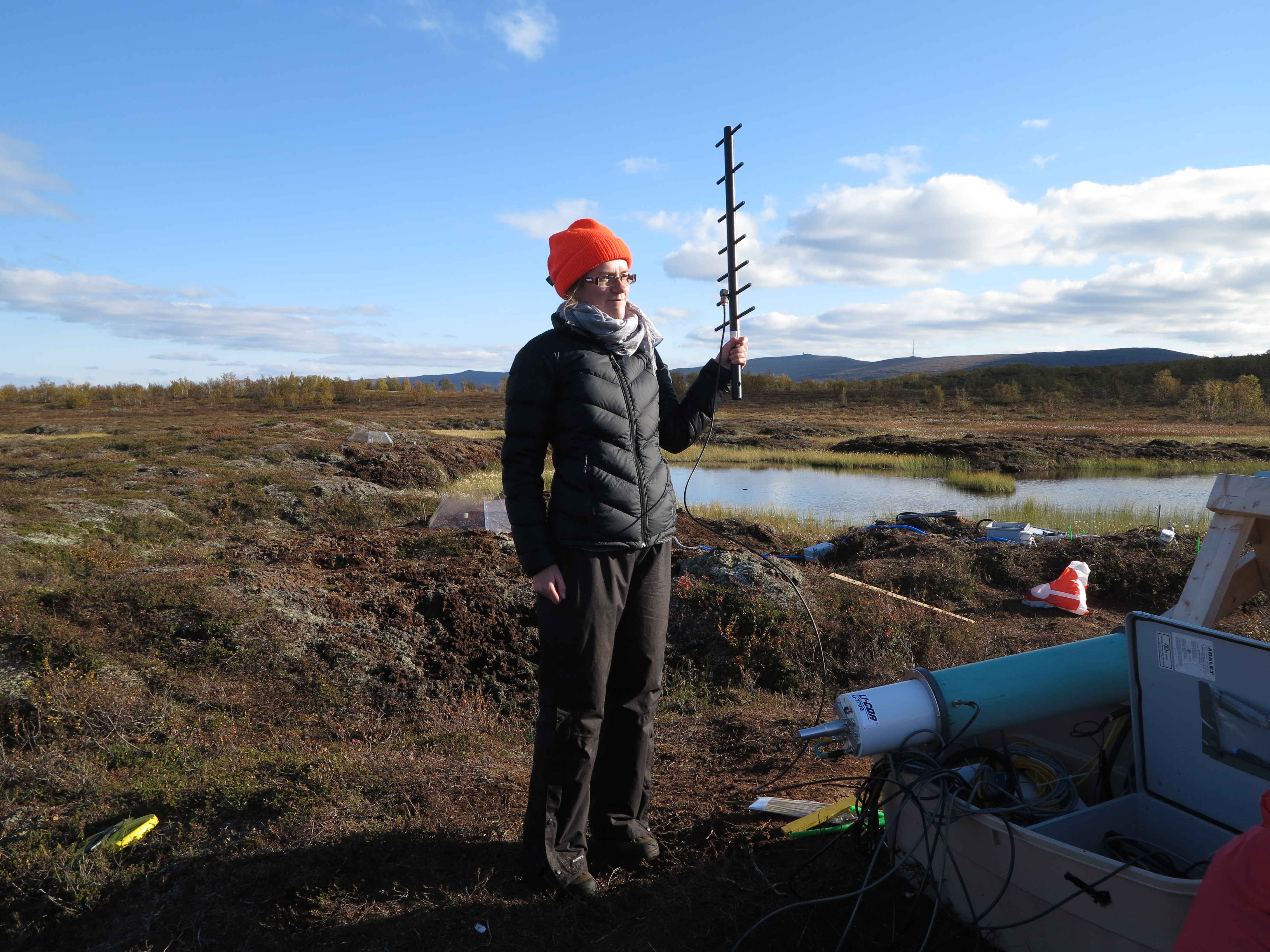

Iskoras is a typical permafrost palsa mire. It’s a patchy landscape with wet, boggy ponds interlaced by dry, raised plateaus called palsas. There’s a lot going on here. There’s permafrost inside the palsa mounds, but not in the ponds. When permafrost inside a palsa thaws, the whole thing collapses to form a pond. Occasionally, new palsas can be raised up and new permafrost can form. This is a dynamic landscape, where the ground can change visibly from one year to the next.

This makes it very interesting to study. For one thing, there’s a lot of carbon in the ground here - the soil is almost entirely peat, which means it’s about 50% carbon, and the peat is several meters deep. From areas like this, a lot of carbon could be released from the soil in the form of greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide and methane. So Hanna and her team are monitoring greenhouse gas production from the surface of the soil and within the soil itself. It’s also an interesting site because in this small area there are lots of differerent conditions: wet and dry, warmer and colder, places with bare soil and covered with plants. So it’s a perfect place for testing out how the gas production changes in different conditions - and so understanding how it might change as the Earth warms and permafrost disappears from the landscape. Sebastian’s team from Oslo are also studying how the palsas collapse and the landscape changes over time, and while we worked they were walking around the site with a gps and altometer, and occasionally a small boat.

There was lots to do in the few days that we had to work. Our group consisted of Hanna - group leader, Casper - postdoc in charge of the site, Renee, a second year undergraduate student from Canada with incredible technical skills, and me - a modeller with basically no experience of fieldwork. Hanna bought us all bright orange ‘safety hats’ since it was the hunting season and she didn’t want any of us getting shot. Here’s a picture of us all with the safety hats:

We replaced faulty equipment, installed a bunch of new stuff, and took manual measurements in places without automatic monitoring. I was excited to discover that physics worked the way I thought it did, and to make some plots of carbon dioxide emissions. I was also given ‘useful’ jobs to keep me out of trouble…

By the time we left, the automatic monitoring equipment was all up and running, and connected to a router so the data can actually be downloaded now we are back at our desks. We had also carried a lot of heavy boxes and bits and pieces in and out of the site, and I am reliably informed, all of the wine was finished off. A successful trip and exciting prospects to do some modelling here too.

It was great to be out in the field instead of the office for the week, commuting to work through shrub tundra, snacking on wild cloudberries and blueberries, surrounded by autumn colours hinting to the coming winter.